in order to help “first post anxiety” i decided to publish one of the first essays that i wrote in first year for a class called “comics & fantasy”. reading it back now it is for sure not my best work but i remember being very proud of myself at the time so i feel like i would be honoring past me by posting it. hope you enjoy :)

“The most obvious trait of fantasy literature is the presence of the impossible and the unexplainable” (Mendlesohn and James).

The earliest forms of fantasy fiction ever recorded are stories about heroes and gods, one notable example being Homer’s Odyssey. This epic poem, which was once part of people’s religious beliefs, follows the journey of the hero Odysseus as he challenges and encounters various mythical creatures such as giants, sorcerers, and monsters throughout the span of ten years. The construction of worlds in fantasy fiction has the power to transport the reader into another universe created by the author, where different cultures, magical creatures, and unique rules exist. This process is not simply telling a story; it’s being transported into detailed imaginary landscapes, where the reader can explore the lives of characters, discover fantastic places and venture into territories filled with magic and adventure. This essay will explore the art of successful world building as it was shaped by Tolkien’s The Hobbit, and how his critique and analysis of Lewis’ The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe impacted their friendship.

In his essay On Fairy Stories, J. R. R. Tolkien distinguishes the difference between fiction and reality with the terms “Primary world” and “Secondary World”, with the former representing the world in which the readers live in, and the latter being the world the author created. An example of a Secondary world is Tolkien’s “Middle Earth”, which he carefully constructed to be the setting of his book The Hobbit, published in 1937.

In his essay “On fairy stories”, he argues that, in order for a fairy story to be effective, the reader must believe that what is happening in the story is true. In this context, 'true' does not essentially mean realistic to the reader but authentic to the secondary world in which the story is set. He goes on to say; “What really happens is that the storymaker proves a successful “sub-creator.” He makes a Secondary World that your mind can enter. Inside it, what he relates is “true”: it accords with the laws of that world. You therefore believe it, while you are, as it were, inside. The moment disbelief arises, the spell is broken; the magic, or rather, art, has failed. You are then out in the Primary World again, looking at the little abortive Secondary World from outside.” (Tolkien 18). Tolkien describes the thin line between the reader and a successful Secondary World. The writer establishes laws in the Secondary world which they have to maintain to make everything “believable” in order to keep the reader inside the world. If this fails the reader is thrown back into the primary world, ruining the reading experience. Tolkien mentions the word “sub-creator”, referring to the author, who is creating a world inside of the universe of the “main creator”, God.

Creating Middle Earth, Tolkien, philologist and scholar, drew inspiration from various linguistic, mythological, and religious sources. Inspired by his own study of language, he took inspiration from Old English literature such as Beowulf and was influenced by Norse mythology and Icelandic folktales in the creation of characters such as Elves and Dwarves. Tolkien redistributed the qualities of the gods in the Norse traditions and used them while creating his own (Sanacore). According to Tolkien, the creation of languages is connected to the creation of mythology; in order for a story to be effective, the languages are the foundation. The invention of a language makes the story more immersive and realistic, something that helps the reader get immersed in the world.

Author Mark J. P. Wolf writes in his book Building Imaginary Worlds: The Theory and History of Subcreation, "For works in which world-building occurs, there may be a wealth of details and events (or mere mentions of them) which do not advance the story but which provide background richness and verisimilitude to the imaginary world. Sometimes this material even appears outside of the story itself, in the form of appendices, maps, timelines, glossaries of invented languages, and so forth. Such additional information can change the audience’s experience, understanding, and immersion in a story, giving a deeper significance to characters, events, and details.” (Wolf 2). When reading examples of the languages the author created, the reader is able to be completely immersed in Tolkien’s world, becoming more connected to the culture the characters are part of. Wolf divides the changes that can be made to the Primary world in the creation stage into 4 different realms, the first one being the Nominal Realm, where things are given a new name (this is the realm in which a new language can be invented). The second one is the Cultural Realm, where everything made by humans is invented, such as customs, objects, ideas, institutions, and so forth. The third one is the Natural Realm, in which not only new landmasses, plants, and animals are created but also new species and races of creatures, like the Hobbits. The fourth and deepest level is the Ontological Realm, in which the basic laws of physics, time, and space are altered, for example introducing new technologies such as time or space travel into the story (Wolf 35).

Wolf goes on to write about relatability, an essential quality that depending on how it’s executed, has the power to improve or be detrimental to the audience’s experience. While an author has the freedom to make as many changes to the primary world as they desire, as shown in the categories of the realms, in order for the final work to be effective, the readers have to be able to relate to the story in some way. When a new species of character is introduced, the author may want to make them anthropomorphic to make their experience more relatable. The world in which the story is set in still has to retain the concepts of good, evil, and causality (Wolf 37). In Tolkien’s The Hobbit, even though the protagonist, Bilbo Baggins, is a hobbit he still shows traits traditionally viewed as human, such as fear and ingenuity. He is home-loving from the Baggins side, his father’s, and adventurous from his mother’s side, the Tooks. The reader can empathise with and relate to Bilbo with the choices he has to make throughout his journey. During the confrontation with Gollum, Bilbo pities him, and, while it would be safer for him to kill Gollum, he shows compassion and decides to spare him (Tolkien 90). Throughout the novel, the main character undergoes a significant development, exhibiting signs of strength and bravery, therefore making it easy for the reader to view him as relatable.

When building the world in the novel The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, C. S. Lewis created a bridge from our world to the Secondary World, bringing the characters from one to another. Different from Tolkien’s universe, the two worlds coexist together; the characters start off in the Primary World and enter the Secondary. The book starts off by introducing four siblings, Susan, Peter, Edmund, and Lucy Pevensie, staying at Professor Kirke’s house. While exploring the house on a rainy day, they discover a room that’s empty except for a single wardrobe. Lucy stays behind to investigate and, stepping into the wardrobe, she finds a wood inside. It is inside that she encounters the first character of Lewis’ Secondary world, a faun called Tumnus, a creature half goat and half man that originates from Roman mythology. After Lucy exits the wardrobe, her siblings tell her that she has been gone only for a few seconds and when she decides to show them inside the wardrobe, it has transformed back into a normal object. The day after, Lucy walks back into the wardrobe and this time, Edmund sees her and follows her. Inside, he meets a tall lady, covered in white fur, with a gold wand and crown in her hand (Lewis 33). The White Queen offers Edmund a Turkish Delight, an enchanted sweet covered in sugar that causes whoever eats it to want more. Allegorically, the White Queen represents temptation and anti-Christian ideas while the Turkish Delight represents gluttony. Just in the first pages of the book, Lewis mixes pagan and Christian elements, something that Tolkien disapproved of and disliked. Tolkien criticised Lewis’ world building, he didn’t like how he mixed elements from different mythologies, like his choice of including Father Christmas, a character which originates from St. Nicholas, a 4th Century Greek bishop, in the same novel as fauns, a Roman mythological creature. The figures he wrote about came from different traditions separated by time and space, a feature Tolkien considered superficial.

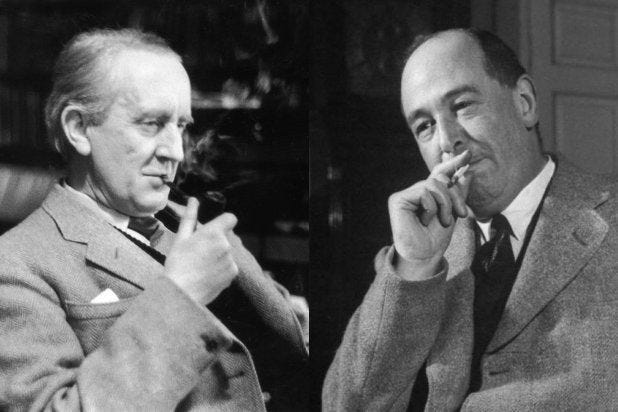

Lewis and Tolkien met at Oxford University, where they both taught. They both were founders of “The Inklings”, a group of writers that met every week and shared stories, debated, and discussed various topics, all while smoking and drinking. Tolkien once wrote to a correspondent that he did not enjoy "stories of an imaginary world that have not got any imaginary history" (Tolkien). He considered Lewis’ world-building to be lacking depth and written hastily. His thoughts didn’t, however, affect their friendship as he still cherished their relationship. He wrote to another correspondent: "I am glad that you have discovered Narnia. These stories are deservedly very popular; but since you ask if I like them I am afraid the answer is No. I do not like 'allegory', and least of all religious allegory of this kind. But that is a difference of taste which we both recognized and did not interfere with our friendship." (Tolkien). Tolkien admits his dislike of the religious allegory Lewis included in his world. This refers to the character of Aslan, the King of Narnia, a powerful and imposing talking lion. He is empathetic and has a strong moral compass, and is so powerful that even just hearing his name, the kids feel strong feelings. His character embodies multiple characteristics associated with Jesus Christ, his wisdom, strength, empathy, and power. Ultimately, he shows his similarity with Christ when he decides to sacrifice himself to save Edmund, and later, in chapter 15 when he rises from the dead. The whole novel has the battle between good and evil as a main theme, with the good prevailing at the end. This is similar to the theme in The Hobbit. Even though Tolkien was a religious man, he rejected any type of allegory present in his work.

In the world of fantasy literature, the concept of world building is a creative skill that draws a line between reality and fiction. Tolkien’s difference between the Primary and Secondary world serves as a main guideline for how the readers are able to understand and relate to different texts. The contrast between Tolkien’s detailed and inventive approach and C.S. Lewis' more varied blend, highlights the different perspectives present in the world of fantasy literature. While Tolkien precisely constructs his intricate mythological worlds, Lewis embarks on a path that mixes different mythological traditions, creating a blend that brings out both appreciation and criticism, especially from Tolkien. Ultimately, the differences between their writing and artistic methods show the complexity of the construction of Secondary worlds in fantasy literature.

Bibliography

Glyer, Diana. “C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, and the Inklings - Official Site.” Official Site | CSLewis.Com, 16 Apr. 2009, www.cslewis.com/c-s-lewis-j-r-r-tolkien-and-the-inklings/.

Grabowski, Daniel. “How J.R.R. Tolkien Built a Language.” How J.R.R. Tolkien Built A Language I Oxford Open Learning, 2023, www.ool.co.uk/blog/how-j-r-r-tolkien-built-a-language/.

Lewis, C. S. The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. HarperCollins Children’s Books, 2023.

Long, Josh B. "Disparaging Narnia: Reconsidering Tolkien's View of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 31: No. 3, Article 4, 2013.

Mendlesohn, Farah, and Edward James. A Short History of Fantasy. Libri Publishing, 2012.

Ruud, Jay. “Aslan’s Sacrifice and the Doctrine of Atonement in ‘The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.’” Mythlore, vol. 23, no. 2 (88), 2001, pp. 15–22. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26814624.

Sanacore, Daniele. “The Norse Myth in the World of Tolkien.” Academia.Edu, 17 Aug. 2016, www.academia.edu/27837783/THE_NORSE_MYTH_IN_THE_WORLD_OF_TOLKIEN.

Tolkien , J. R. R. “Letter to Mrs Munby.” Tolkien Gateway, Tolkien Gateway, 20 Sept. 2022, tolkiengateway.net/wiki/Letter_to_Mrs_Munby.

Tolkien, J. R. R. The Hobbit. HarperCollins, 2011.

Tolkien, J. R. R. “Letter to Eileen Elgar (24 December 1971).” Tolkien Gateway, Tolkien Gateway, 30 May 2014, tolkiengateway.net/wiki/Letter_to_Eileen_Elgar_(24_December_1971).

Tolkien, J. R. R. “On Fairy Stories - Wordpress.Com.” On Fairy Stories, 1947, coolcalvary.files.wordpress.com/2018/10/on-fairy-stories1.pdf.

Wolf, Mark J.P. Building Imaginary Worlds the Theory and History of Subcreation. Taylor and Francis, 2014.

This was actually really great, you definitely put the time into this and I love how you put your heart into this. 10/10

Lovely! I love Narnia so, so much. Never did the LOTR dive, but I've heard it's got similar traits. Great work! <3